A Gender Lens in Eugenic Higher Education History Analysis

Anna*, a junior at Vassar, highlights how her research on the history of eugenics at Vassar reveals the imperative to consider gender in eugenic higher education analysis.

*Anna L. Philippe ‘27 (she/her/hers) is an undergraduate student at Vassar majoring in Educational Studies.

My work on eugenics so far has focused on Vassar College, where I am a current student. Coincidentally, Vassar and Yale share some history: A proposal for Vassar to move to New Haven to become Yale’s coordinate women’s college surfaced in the 1960s, but Vassar rejected the proposal in 1967, and both schools became co-educational in 1969.

Important to my research is that Vassar was an all-women’s institution during the peak of the American eugenics movement from the late-19th to mid-20th centuries. Thus, much of my inquiry focuses on the gendered axis of eugenics, exploring how female student bodies were scrutinized in pronatalist eugenics discourse. The work has revealed to me the necessity of a gender lens in eugenic higher education analysis. Put simply, eugenics appeared differently in Vassar’s history than it did at Yale’s. Why?

Eugenics at Vassar

For context, my work on eugenics at Vassar demonstrates that the College offered eugenics an academic license in several ways. To name a few, eugenic teachings appeared consistently in events and reading lists; the College invited such notorious eugenicists as Margaret Sanger and Charles Davenport to speak on campus; and an ongoing relationship with Davenport helped establish a career pipeline between Vassar and his Eugenics Record Office (ERO), the epicenter of American eugenics research. As ERO fieldworkers, some Vassar alumnae collected data “on vast numbers of so-called mental and social defectives” that became the “backbone of U.S. eugenics” and legislation on sterilization and immigration control.

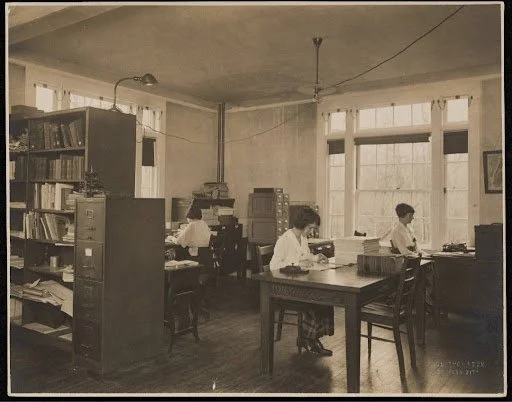

The Eugenics Record Office in the 1920s. (Source: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory and the Eugenics Image Archive, Dolan DNA Learning Center.)

But eugenics isn’t just a matter of studying and limiting reproduction of the Other (negative eugenics); it also necessarily becomes a mechanism of control over the bodies of people with ostensibly desirable genes (positive eugenics). Positive eugenics is pronatalist, often encouraging reproduction in ways that reinforce reproductive injustice, heterosexism, and patriarchy. If a better race is to be constructed, it is female bodies who ultimately host the construction. In this sense, eugenics is as much about gendered control as it is about racism, ableism, or classism. Hence, an effective analysis of eugenics in higher education history must interrogate this gendered axis and draw relevant distinctions between the expression of eugenics in women’s versus men’s colleges.

Women’s colleges as targets for eugenic pronatalism

While Vassar welcomed much antinatalist dialogue, the dialogue regarding the College’s own students was sharply pronatalist. Vassar students, who were largely white, affluent, and able-bodied, were the subject of eugenic pressures to reproduce.

Academia became both the object and the platform for pronatalist arguments, with scholarly writing legitimizing population anxiety. For example, a 1915 article in the Journal of Heredity titled “Education and Race Suicide” lamented that only 53% of Vassar alumnae of the classes of 1867–1892 had married, and, on average, had only one child. Just months later, another Heredity article posited, “The extraordinary inadequacy of the reproductivity of these college graduates can hardly be taken too seriously. These women are… from a eugenic point of view, clearly of superior quality.” Still another referred to the women’s graduate birth rate as “the most pathetic spectacle of all.”

1915 Journal of Heredity article headline.

Education, eugenicists thought, was the root of the problem. “Instead of education for motherhood,” wrote eugenicist Samuel J. Holmes in 1928, “the fine young ladies attending these excellent institutions are being educated for race suicide and a career.” Co-authors Roswell H. Johnson and Bertha Stutzmann thought that excessive limitations on students’ social lives and lack of coeducation were to blame for the low birth rates. Essentially, they asserted, women’s colleges were failing to facilitate sex. They also postulated the failure of colleges to instill in alumnae the desire to become homemakers, as though that should be a primary object of women’s higher education. Soon, efforts were indeed made to educate women towards domesticity. As a 1926 New York Times article reported, “Vassar girls” were to begin “to study home-making as career” through the “new course in euthenics,” said to “adjust women to the needs of today.”

Pronatalism and higher education today

The century-old discourse on college-educated women’s birth rates mirrors current pronatalist dialogue, albeit today’s is more explicitly policy-oriented. As a 2024 report from the Heritage Foundation—strategists of Project 2025—titled Education Policy Reforms Are Key Strategies for Increasing the Married Birth Rate states, “government interventions in education are, whether intended or not, pushing young people away from getting married and starting families—to the long-term detriment of American society.” It’s recycled rhetoric for a new political moment: blame it on schools that educated women aren’t reproducing enough, and find ways to reinstitute gendered control. The solution now, as critic Darby Saxbe summarizes, is to “get those youngsters out of school and into baby-making mode.”

More specifically, the Heritage Foundation report proposes 1) adopting universal school choice to expand access to private and religious education, 2) eliminating teacher certification requirements that “delay family formation,” and 3) ending student loan cancellation, which “signals what Americans should do upon high school graduation,” among other recommendations. In short, the current pronatalist agenda requires the erosion of education reforms across multiple policy arenas and the introduction of what the report calls “key pro-fertility policies.” Obviously, this implicates both women and men, but women are often the most vulnerable targets of such population politics.

Moving forward with a gender lens

As education persists as a site for pronatalist (and arguably, eugenic) discourses on reproduction, a gender lens of analysis remains necessary. Anyone curious about the expression of eugenics, past or present, should consider how gendered contexts mediate eugenic realities and discourses. Eugenics isn’t just about demographic control as an abstract, but reproductive and social control as an embodied reality, especially for women.

Importantly, increased focus on gender should not replace sustained attention to race, ability, or class. An intersectional ethic should be used to elucidate the simultaneous relevance of multiple positionalities with regard to eugenics. Only this way can we most completely understand the historical and present relationship between eugenics and higher education institutions.